Interview

Remix

November 2008

The medium and the message are never separate in the music of Matthew Herbert. Spun partly from esoteric samples — the sounds of laser eye surgery, drums recorded in a hot air balloon or condoms dragged across the floor — his songs appear to be some form of sonic alchemy or voodoo, but every note and noise fits into a larger political context. It’s part statement, part adherence to a code (Herbert’s Personal Contract for the Composition of Music) and partly a play on the storytelling potential of audio over visual.

“People have a very different level of expectation and cynicism when it comes to sound,” Herbert says. “I think this obsession with the image is at the heart of what’s wrong with our society.”

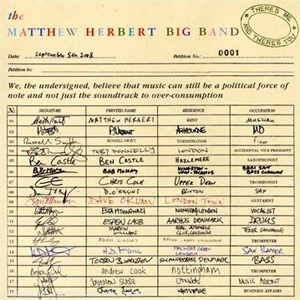

But behind the philosophical rigor, post-modern critiques and stunt sampling lies an appreciation for the art and craft of recording. Herbert’s latest, There’s Me and There’s You (!K7) fuses experimental samples with a big band. While he and the engineers he works with are rigorous — 13 tracks were recorded in one meticulously planned day at Abbey Road Studio Two — he can also be incredibly flexible.

“I tread a very fine line between absolute precision and couldn’t give a shit,” he says. “I’ll spend a great deal of time researching the right mics for trombones, and then I’ll happily turn up at a session and record with my mobile phone. It’s much more about the story than the intention of the music.”

Varying circumstances and equipment contribute to this sampling-as-storytelling approach. Herbert uses anything from disposable MP3 players to his Apple PowerBook’s built-in mic (using a Prism Sound Orpheus interface and Logic 8) to the Nagra V portable audio recorder. Because many of his samples are one-off — for example, people cutting up 100 credit cards — he needs plenty of options and backup when mixing. The track “Waiting” contains samples clandestinely recorded at the Houses of Parliament, after Herbert’s attempts to get official permission were bogged down in bureaucracy. Instead of properly setting up, he secretly used a Nagra SN stowed in his pocket so the muffled samples, in part, communicate the recording’s circumstances along with a political point about access. Meanwhile, the pulsing beat of “One Life,” made from the sound of an incubator that kept Herbert’s infant son alive, comments on the Iraq war, since each beat represents 100 Iraqi casualties (it proved impossible to make a track with one beat per fatality). “Nonsounds” addresses the Israeli-Palestinian conflict both structurally — all the musicians were recorded separately in their homes, to mirror the separation caused by security measures — and sonically, since all the samples were provided by Palestinians and recorded by engineer Waleed Ajel.

The jazz musicians presented different challenges. Herbert wanted to set mics far enough away from the ensemble so he could capture the correct acoustical blend of the instruments, yet not too far away that he missed details. His solution — built around the idea of having as many options and inputs as possible — started with placing the band in one end of the studio with carpet laid down on the floor to control reflections from the ground. The key was placing a stereo pair of Neumann M 50s just behind the conductor. This was the spine around which everything else was built. Another pair was set higher and farther back to capture more of the room. A Decca Tree trio of RCA 44BX ribbon microphones was arranged a bit farther forward to capture a bit of the top end, and each of the instruments were individually miked (saxes used Neumann U 67 mics, trombones and trumpets used Coles 4038 Ribbon mics).

The vocalist, Eska, was recorded at Herbert’s home studio on Lomo microphones, specifically the 19A9. They have the warmth and character to match the charismatic singer and a solid mid range and a crunch that can compete with blasting trumpets. The Lomo 19A19, with crisper top end and warmer bottom end, was drafted for backup vocals, which Eska also provided. When recording vocals, Herbert doesn’t use a control room or wear headphones — he literally sits next to the singer. It “becomes a very easy musical conversation,” he said. This method also captures anomalies, like the faint sound of a train on “Waiting.” For someone so deliberate, these real moments are the ones he savors (his label is called Accidental, after all).

“They annoy you originally,” Herbert says. “Oh shit, we recorded a bloody train. But they’re the bits when music gets exciting, the bits we could never re-create.”