Review

Playboy.com

May 2007

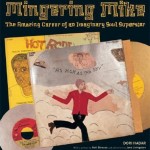

Mingering Mike: The Amazing Career of an Imaginary Soul Superstar

By Dori Hadar

Princeton Architectural Press, 192 pages, Paperback $24.95

Record collectors live for the moments when obsessive hunting for rare vinyl unearths an undiscovered treasure. Dori Hadar, a Washington D.C. criminal investigator and DJ, discovered a different kind of rarity while digging through music at a flea market a few years ago. Browning at the edges and wrapped in plastic painstakingly removed from other albums, he found a series of meticulously hand-drawn record covers filled with blank cardboard discs. These dummy releases were examples of the work of unlikely D.C. artist Mingering Mike, a life-long music fan who channeled his passions and “creative juices” into a vast, fake discography. Mingering Mike: The Amazing Career of an Imaginary Soul Superstar, is Hadar’s retrospective on this shy and introverted artist’s career and an homage to cover art at a time when digital distribution is eroding the medium.

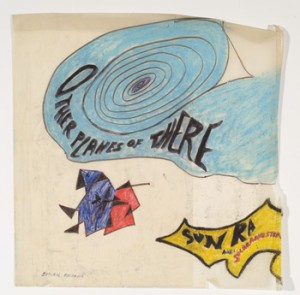

Mike’s work is a rich homage to familiar themes, a DIY collage of re-imagined funk and soul clichés. Fake blaxploitation film soundtracks (Stake Out) sit next to albums of social commentary (Drug Store). There are catalogs of records from imaginary labels like Spooky, Sex and Nation’s Capitol that would be great subjects for a Numero Group reissue, and some of the promotional lines adorning the labels are hilarious (“Ohio Players Eat Your Hearts Out,” or “It’s so brilliantly good, they couldn’t help but put three albums in this pack”). A few essays and an interview with Mike provide the necessary background to appreciate Mike’s art.

Based on his prolific output, varied roster and sales figures — when you’re playing games, why not go platinum? — Mike would have made Barry Gordy jealous. But his hyperbole and fake career wouldn’t have been as powerful if he didn’t allow reality to seep in. Many characters on his albums were named after or inspired by friends and family, and one live concert album was recorded at the famous Howard Theater, only miles from his D.C. home. Mike’s experiences being drafted and then going AWOL in boot camp in 1970 inspired a series of anti-war covers, including The Two Sides of Mingering Mike, which dramatically depicts the divided singer, one hand reaching for the microphone and one reaching for a rifle. Like some Harvey Darger for the crate-digging set, Mike used the medium of cover art as a way to create a rich fantasy world partially based on his own experiences.

Mingering Mike has kept up with technology and created a MySpace page, which includes samples of his recorded work. The crude a cappella tracks — he can’t play an instrument and hums all the melodies — are revealing, but diminish his charm. Hearing an actual Mingering Mike track takes away from the mystery. His cover art was so visually distinct and poignant, viewers’ minds could run wild, imagining what untethered soul and funk was playing in his head while he was drawing.