Feature

EQ

June 2010

Link

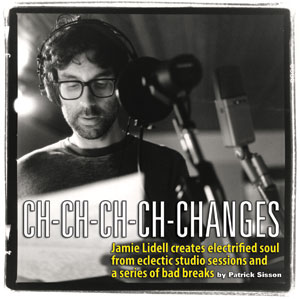

Compass, the latest album from live-wire musician Jamie Lidell, finds the pitch-shifting, melody-looping extrovert experiencing a catharsis. Grasping for solid ground after suffering what he calls a “triple whammy”—the dissolution of a relationship, a change in management, and a move from Berlin to New York— he set down and in the course of a month, wrote his own version of “good, old-fashioned relationship blues.”

“It left me to reinvent myself with all the joy and pain and the freedom to think and deal with the fear and shit that got stirred up,” Lidell says. “It’s the deepest blues I’ve ever felt. But music is a really sweet healer.”

Raw performances aside, the classic sentiment expressed throughout Compass [Warp] was built from technology-enabled, studio-hopping collaborations. Production was done at multiple studios. There were collaborations with Beck and others at the famed Ocean Way complex in Hollywood. Meanwhile, musician Chilly Gonzales and Wilco multi-instrumentalist Pat Sansone contributed backing parts remotely via online file sharing, and Lidell recorded synth parts on his Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 in his apartment.

Sessions also took place at Leslie Feist’s Canadian home in the Niagara Escarpment, with production and mixing help from Grizzly Bear’s Chris Taylor.

There, the trio utilized space and texture in creative ways, such as creating natural reverb by playing trumpet off into the wilderness while miking the sound from the other side of the cabin.

These personal songs aren’t the work of a knobtwiddling one-man band. “The whole album’s approach is about finding acoustic solutions,” Lidell says. “There’s not much electronics going down.”

However, Lidell’s flexible, expressive voice did take center stage once again. Befitting the regret-to-rage spectrum of emotions expressed on the album, a variety of approaches were used to capture raw vocal performances. All were sent through a Neve 1081 EQ. But while working at Ocean Way with Beck, Lidell used a Neumann U 47 sent through a Neve 1271 preamp for a “classic, Nigel Godrichesque chain,” or an Altec 693, a “skull-shaped” dynamic ribbon mic, which gave the title track’s vocal a creamy, dark sound. But for something with more edge, he favored an AKG/Telefunken D 19.

“It’s just a really aggressive mic that gave me all the bite I was looking for,” he says. “It has presence. I like to do overdubs with a little more burn on them. It’s so flattering in a way, but also sounds blank, like it’s already EQ’d.”

To add more depth, vocal recordings produced at Feist’s ranch were also threaded throughout the album. Taylor set up multiple mics in a cavernous, open part of her house to record and blend multiple mic inputs. A Shure SM7 captured the “meat-and-potatoes” of Lidell and his collaborators, including Feist, while Sony C-48s were placed at different heights and distances to allow for a more three-dimensional sound during mixing. The unique Grizzly Bear acoustics and composition are also present on “The Ring,” a thumping piano stomper that includes a rippling, pentatonic-style guitar riff from Daniel Rossen.

Heavy use of distortion reinforced Lidell’s mindset and lyrics throughout the album. The Thermionic Culture Vulture was responsible for much of the bending and shaping of sounds. “It’s such a rewarding box,” he says. “It allows you to re-sculpt distortion, and even though so many sources behave so differently with it, it’s still intuitive. Everything works in the mix. It’s a brilliant go-to box. In a whole way, the nature of the messages and lyrics requires a darker, more eroded sound.”

A weighty set of booming drum and bass rhythms also showcased Lidell’s darker moods. Recorded mostly at Ocean Way, the drum and bass benefited from the intimate knowledge Beck and players like drummer James Gadson had of the space and the gear. Though they spent two days in the studio, a bulk of the rhythm tracks came out of those sessions. According to engineer Robbie Lackritz, Gadson played a set of custom Pearl Drums in an isolation room. It was extensively miked: U 47s, C 414 with C 12 capsules and Josephson on the snare, an API Sidecar and 1073s for preamps, and very little compression. The close mic setup captured a tight, rich sound, which was tracked to Pro Tools and doubled up on the APR 24-track.

Lidell took advantage of tape recording, both at Ocean Way and via his Nagra portable recorder, to capture unique textures and create echo effects. He drafted the ATR tape machines into service as a very expensive delay effect, threading the tape into the custom board and then back into the ATR.

“It’s an expensive, naughty way to use the machine,” he says. “It was common back in the day, of course. When it starts to hit itself, it’s insane, proper goose bumps kind of sh*t. It was a more complex live task, but it was a nice way of adding effects.”

The portable Nagra captured drum sounds, the odd cowbell, and even trumpets. “The Nagra captured this strange distortion from the quick distortion of tape,” he says. “The way mallets sound on tape is great. You also get the joy of a really aggressive sound into the mic, pushing air, capturing it on the tape. That mid-range power was great. With a trumpet, for instance, you don’t want it to be polite—you want it burning.”

The communal and experimental elements of the album came together for the title track. Sitting in a circle and working from a simple song sketch, Lidell, along with Feist, Beck, and Nikka Costa, were strumming guitars or singing into a set of U 47s, recording without any separation. It frustrated Taylor when he went to mix the album, but ultimately the space and setup defined the song’s brash, western drift.

“There was no way to remove the bass track on the guitar, which made it cool,” Lidell says. “You just had to embrace the guitar playing. It was a little shaky, but that was kind of the mood. As you’re working with the song, you have to f*cking go for it. There’s something really beautiful about that.