Article

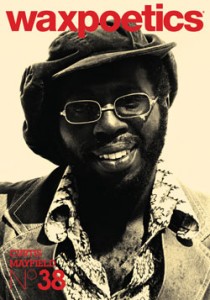

Wax Poetics

Issue #38

Link

A camera can be an annoyance or it can mean access. For Chicago photographer Michael Abramson, his 35mm Leica M3 was his way to penetrate the curtain of clubland and document a world both public and private.

“Nightlife is eternal,” says Abramson. “It went on 100 years ago, and it’ll go on 100 years from now. We’re not talking about palatial nightlife. We’re talking about the little conversations, people trying to have a good time, trying to score. I’m sure it’s happening now.”

His camera and curiosity helped propel him into South Side Chicago nightclubs in the mid-‘70s. Functioning as part participant and part documentarian, he created a striking body of black-and-white images collected in the new book Light: On the South Side. A cache of fleeting moments and forgotten nightclubs, Abramson’s work is the flipside of self-serious documentation. The people, from patrons to bartenders, are the focus, not the performers. Exuding sharpness, rich skin tones, grain and detail, the photography is lush, aided by the occasional use of extra lights. Subjects look back from the page, inviting readers to concoct the story of that evening’s events. The photos don’t just frame a scene from a culturally distant time. They heighten the electricity, small triumphs and hidden glamour of life after dark.

“This was my experience at night time,” he says. “I didn’t know the South Side of Chicago. And maybe, in retrospect, that’s when great photos happen. When someone says to you, what were you doing on the South Side, the inference is, if they were doing it, they’d have some set mindset. I didn’t have any set mindset.”

Abramson arrived in Chicago from Boston in 1974. He moved in the near north suburb of Evanston and pursued photography at the Institute of Design. A roommate tipped told him about club called Pepper’s on South Cottage Grove Avenue, in Chicago’s predominantly African-American South Side, and Abrahamson, restless to explore, decided to show up with his camera unannounced.

“It was a scene, but not much was going on that night, so I thought I should go somewhere else,” he says. “Then I walked out and someone said, ‘Hey, where are you going?’ [Owner] Johnny Pepper said that he said it. I’m not sure that’s the case. But that pulled me back inside and started an odyssey.”

From 1974 to 1977, Abramson worked within a tiny radius of smoky clubs up to four nights a week. He’d hang out, snap photos and leave around 2 a.m., stopping for a late-night cup of potato soup on his return trip north. Many of his pictures were printed off a kitchen cupboard converted into a darkroom and developed in a basic, unventilated darkroom, with plastic over the doorway. A portfolio of bartenders, barflies, dates and dancers, Abrahamson’s work is filled with evening ephemera—tables filled with Salem cigarettes, Schlitz beer bottles and setups of Crown Royal whiskey and ice, or two dancers, beaming at each other’s embrace. Portraits and perspectives — like a train rumbling past the Patio Lounge or Magellan the pimp stirring the last ice cubes in his highball glass — highlight the details and characters Abramson drew from his setting.

“You’re going to have fun at a club with music, booze and girls, but you’ll have more fun because you have a reason to be there,” he says. “Anybody could end up there. People say, ‘Did you feel weird being a white person?’ I wasn’t the weirdest person at these places.”

Abramson occasionally hit up joints like the High Chaparral or the Jazz Showcase Lounge, but most of his time was spent inside two nightspots. Perv’s House, a funeral home turned flashy private nightclub and a frequent hangout for cast member of the Chicago version of Soul Train, was run by gospel scion Pervis Staples. Pepper’s Hideout, a low-ceilinged lounge run by serial nightclub owner and former Ford employee Johnny Pepper (Robinson), featured blues acts like Arelean Brown, Lonnie Brooks and Mack Simmons, who had standing engagements. But patrons at these nightspots might also see a kid’s talent show, a transvestite review or a DJ night hosted by the Sexy Mama’s Social Club.

Abramson used these photos for his thesis, comparing them to the work of forbearers like Brassaï, documented nocturnal Paris in the 1920’s. He earned an NEA grant for his work and eventually became a commercial photographer, but apart from a few brief gallery shows, his South Side work never got widespread exposure. A 2008 Chicago Tribune article about the photos set off Numero Group’s radar. Abramson jokes that when the label’s cofounder Tom Lunt sent him an inquiry email signed “Minister T,” the photographer originally thought he was being solicited by the Nation of Islam. After a year of work, the monograph is being released, packaged in a slipcase with a two-LP set of Chicago blues, called Pepper’s Jukebox, filled with tracks that capture the in-between sound of the genre’s mutation from sharecropper laments to big-city groove, according to Numero’s Ken Shipley.

“We started to think how could this be more interesting, what do these picture sound like?” says Shipley. “We started looking at the posters and the ephemera that Michael brought over. It showed us where we needed to go. It was much easier to build the music once we realized this was a very musical world. This is the soundtrack to these people’s night out.”

Much of the power of the images comes from the temporary nature of the situation, scene and fashions they document (Pepper’s had become the Zodiac before Abramson finished his project). After the Tribune article was published, one of Pepper’s daughters got in touch with Abramson, and he eventually ended up meeting up with an 83-year-old Johnny Pepper at his daughter Alicia’s wedding at a suburban country club in South Holland. Abramson handed Pepper a copy of the music Numero had compiled for the release, and he verified that those tracks were at, one time or another, on his jukebox. According to Abramson, Pepper tried to get the wedding DJ to play the tracks, but the DJ looked at him like he was a crazy old man. Not suitable treatment for a music supporter and father of the bride, but perhaps just another symbol of the fleeting magic of a night out.