Feature

EQ

January 2011

Link

Last October, Gang of Four guitarist and producer Andy Gill delivered a lecture on recording to students at the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts. The influential post-punk guitarist wasn’t afraid to be self-effacing: He played one of his band’s lesser-known songs, an early ’90s cover of Bob Marley’s “Soul Rebel,” and asked students to tell him what was wrong. He waited until one said it sounded like “catwalk music” before he agreed.

“[Complex production] can sound amazing, and the programming can be fantastic,” says Gill, “but to me, it’s falling in love with the samples and MIDI programming and forgetting what you’re about. It’s not Gang of Four music. It could be great for something else.”

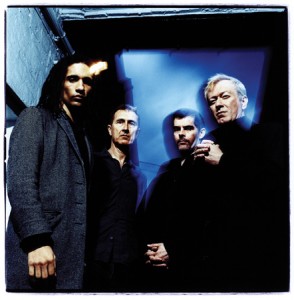

Content, which Gill recorded over the past two years at his own Beauchamp Studio in Central London, is a return to form—aggressive, prickly, and muscular. Gill worked over song ideas with founding member and vocalist Jon King, perfecting tight, rhythmic arrangements before bringing on newer members Thomas McNeice (bass) and Mark Heaney (drums) for recording.

“One of the beauties of guitar/bass/drums is you have a lot of space,” says Gill. “More traditional pop music has this hierarchical, pyramid structure, with lead vocals on top, guitar below it, and then keyboards and backing vocals, all meant to support the lead vocals. One of the things Gang of Four did was put everything side by side. It all worked together and created a rhythmic network, which fed into our aesthetic ideas.”

A signature aspect of Gang of Four’s style is Gill’s “shards of sound” guitar technique. Influenced by Hendrix, the jerky playing of Dr. Feelgood’s Wilko Johnson, Steve Cropper of Stax Records fame, and blues icons like Howlin’ Wolf, Gill played through transistor amps, as he did on 1979’s Entertainment and 1981’s Solid Gold (in this case, either a Peavey Classic 50 Combo or Blackstar Artisan 30).

“Everybody looked down their nose at me, because proper musicians are supposed to use valves,” says Gill. “That’s always been the case. I liked the coldness, if you like, of transistor amps. With the Fender Strat and the PV combo, you can get a thinness of sound. You don’t end up with the big, fat Marshall distorted sound. It’s thin, bright, and sharp.”

Gill routes his Fender Strat with Lace Sensor pickups (which result in less buzz when gain is added) through a DI, sending one signal straight to Logic and the other through the amp, blending the amp mic tracks with a track modified with plug-ins, including the Logic amp simulator or Pedalboard. On the Peavey, for example, he normally places Latvian-made JZ mics such as the uniquely-shaped Black Hole or the BT201 as a pair in front of the amp, and then maybe a Neumann U67 in the back for room sound. “I find that quite exciting, switching between them,” he says. “If you record those mics in the mix, you can cut one out and bring another in and automate the levels. It’s a bit like the dub techniques; it helps drive the narrative of the song.”

Gill’s dry, rhythmic, and cutting sound—he describes a certain frantic section of his playing on “Do As I Say” as him “setting fire” to singer King— doesn’t rely on compression or many pedals, though he will use the Boss SL- 20 Slicer. His only “vice,” as he describes it, is tremolo, especially the effect on the Boss pedal. He can lock to the track via MIDI and program different rhythms within the tremolo, which you can hear on the vibrating, flinty intro of “She Said.”

“When I’m recording drums, I use compressors, because I know what I want and I want to get as close to that sound as I can when I’m going in,” says Gill. “I don’t want a natural sound. I’m not a jazz guy who sets a few mics around the room. I want my drums to sound big. I always listen to the drums as much as anything else. I get off on great-sounding drums.”

On Content, Gill surrounded Heaney’s PDP kit with various mics, including a pair of Curtis valve mics hung three feet above the kit for overhead coverage; he found them crucial for the right tom sound. The kick drums and snare were close-miked from various angles and sent through a variety of compressors (UREI 1176, dbx 160, and a PYE model from the ’60s), and Gill would ride up the room sound for extra emphasis. The kick had a D112 inside and either a Neumann 47 or 67 outside, usually placed about one-and-a-half or two feet away. “For the snare, I use an SM57 or Beyerdynamic M88, an SM85, and a KSM44,” says Gill. “The 44 I usually put close and send through a Transient Designer for more whack and crack; it gives it character. Any mic under the snare will do, just to add to the rattle.”

The album was rounded out with King’s vocals, captured on a Shure 57 or Neumann 67 and given a touch of delay and reverb with the PCM 70 or 80 and Logic reverb, “to help the vocals sit in the track.” Sometimes Gill would set up a bus within Logic to send vocal tracks through a load of distortion or send it through a high-pass filter to take out everything over 300Hz. With trademark politically charged lyrics, the relatively unadorned vocals don’t muddle the message.

It’s clear that the work of these Leeds University classmates still resonates. And while Gill’s work as a producer of the last few decades has included sessions with bands ranging from the Red Hot Chili Peppers to the late INXS singer Michael Hutchence, it’s exciting to hear him back with his original band.