Feature

Pitchfork

December 18, 2009

Link

18. Atlas Sound

Logos

[Kranky]

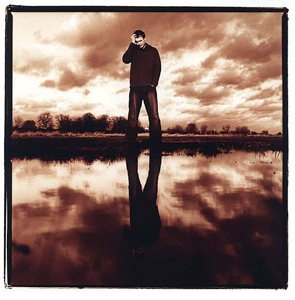

While it has plenty of watery drips and washed-out backdrops, Bradford Cox’s Atlas Sound project can also be very blunt. Like his work with Deerhunter, he places gothic horror side-by-side with gorgeous guitar riffs and sonic textures, a disarming combination. But Logos makes it a point to get dark. Guilt and suffering are commonplace; it’s suffocating to enter the album’s lyrical landscape of cold lights, grey dawns, and regrets. The simple line “my halo burned a hole in the sky” is stigmatizing.

Logos is another turn at making pop music wrapped in sonic gauze, yet all the wounds remain exposed. Just look at its cover; Cox’s own frail, caved-in chest contrasts with a face obscured in a blinding light. But the aura and the album are also revealing and redemptive. “Shelia” spins an elderly couple’s burial into something poppy and romantic. Saints aren’t born saints, Laetitia Sadier implies in “Quick Canal”, later cooing that “wisdom is learned.” Perhaps it’s all about moving toward change. As the refrain says on “Walkabout”, the album’s propulsive and sunny highlight, “Forget the things you’ve left behind/ Through looking back you may go blind.” –Patrick Sisson

9. Fever Ray

Fever Ray

[Mute/Rabid]

When the first singles for the Knife singer Karin Dreijer Andersson’s Fever Ray dropped, it was clear that her solo project was inscrutable, even by the standards of someone who considers Venetian plague masks a cornerstone of her wardrobe. The first impression is that atmosphere trumps narrative; bass notes, simple rhythms, and stark synth chords creep like a rolling fog while a cast of pitch-shifted voices emerge from dark corners of the woods or darker recesses of the mind. But Andersson’s use of chilling childhood imagery and warped lyrics, filled with morphing perspectives that cultivate curiosity and raise questions that may never be answered, make it addictive. Who knew dishwasher tablets could be so unsettling?

What’s made Andersson’s work even better is how her videos and performances amplify the music’s sense of dread and mystery. Does the dirty rave dancer on a diving board know she’s being watched (“When I Grow Up”)? Why is the Miss Havisham figure in a silver dress cavorting with farm animals (“Seven”)? Are they the same person? It’s deliberate, theatrical smoke and mirrors, constant reinvention, and a David Lynch-like veneer of unseen danger that invite audience reinterpretation. The more material this unique artist releases, the less any of it makes sense. –Patrick Sisson

Read the complete list here.