Curbed

Pay a visit to Petronia Street in Key West, Florida, on a summer day, and density quickly becomes apparent. The humid air, a palpable weight, begins dragging you down by mid-morning.

History starts making itself visible. The eastern edge of Petronia almost backs up to the island’s above-ground cemetery, which holds generations of soldiers, settlers, and everyone in between—an everlasting last call in a city that self-identifies as the Conch Republic.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236233/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_04.JPG)

The western end of Petronia forms what was once the border of Bahama Village, the center of the city’s Afro-Caribbean culture since the 1800s, once home to a famous open-air flea market and a potent blend of black, Bahamian, and Cuban influences.

Long since discovered and commercialized, Key West is facing a dilemma common to tourist markets across the country, driving locals to the edges of, and eventually away from, the town they once loved. The myth of Key West has made the reality of Key West increasingly unaffordable.

In the middle of Petronia Street, in a reclaimed clapboard house on the corner of Thomas Street, Blue Heaven restaurant has offered a picture of the neighborhood since it opened in 1992. Inside the gravel yard, beneath palms and almond trees, sits a small bar, an even smaller stage that looks like a glorified shipping palette, and a rooster graveyard.

/cdn1.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236239/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_05.JPG)

/cdn1.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236241/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_06.JPG)

It’s a peaceful spot for someone tired of the cruise ship crowds mobbing Duval Street, the island’s tacky tourist funnel. The gravel yard where diners eat outdoors year-round has had its own colorful life over the last century, including stints as a bordello, a cock-fighting arena, and even an impromptu boxing ring (where Ernest Hemingway supposedly refereed Friday night fights).

As he does many afternoons after work, local writer Michael Ritchie grabs a stool at the bar. Ritchie moved to Key West in 1993 after visiting on vacation, and quickly found a room for rent via the “coconut telegraph,” island slang for the local rumor mill.

A longtime journalist, Ritchie has reported for newspapers and self-published his own series of historical novels. He hasn’t reached native status—those born on the Keys address each other with the informal “Bubba” or “Cuzzy” title—but, in effect, lives the dream that brings so many to the island.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236243/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_30.JPG)

Ask him about that choice now, after 23 years, and the siren song that led Ritchie here isn’t playing anymore. “As soon as the banking system is set up,” he says, “I’m moving to Havana.”

“The realtors came along and started telling people, the property you’re sitting on is really valuable,” he says. “Everything is going to change, it’s inevitable.”

The shift, according to Ritchie, is about rarification, not just gentrification, and you can see its legacy all along Petronia. Former single-family shotgun homes are now renovated winter homes or guest houses rented to tourists.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236245/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_14.JPG)

“The attractions that made the city so quaint have been taken over by the cruise ship people,” says Ritchie. “In season, we have four, five, even six ships a week. It’s great for making money, but it’s ruining the quality of life for many of the residents living here.”

At the corner where Petronia intersects with Duval, three drag queens are parked in front of the 801 Bourbon Bar, hawking flyers for a drag show later that evening. Mulysa is out with her friends, Shiva and Sasha, greeting the curious and defending “our corner” from the occasional gawker or rude tourist (“all while wearing my six-inch heels, my sensible shoes”). Mulysa came down to visit from Boca Raton, Florida, ten years ago, and within a few weeks, found a house and moved in.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236247/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_03.JPG)

“When I first came here from New Jersey, this place was a lot more gay,” she says, with a break to take a photo with a visiting family. “Now they’ve made it so commercial.”

To Mulysa, Key West offers something simpler, a “small town on steroids.” Everyone knows everyone, for better or worse, but she’s had enough. It’s a lovely town, she says, but at this point, her liver hurts.

All along Petronia Street, real estate pressure is slowly shaping and molding the city into something different. The push of mass-market tourism and luxury homes is the backdrop for most discussions among local government officials and area developers.

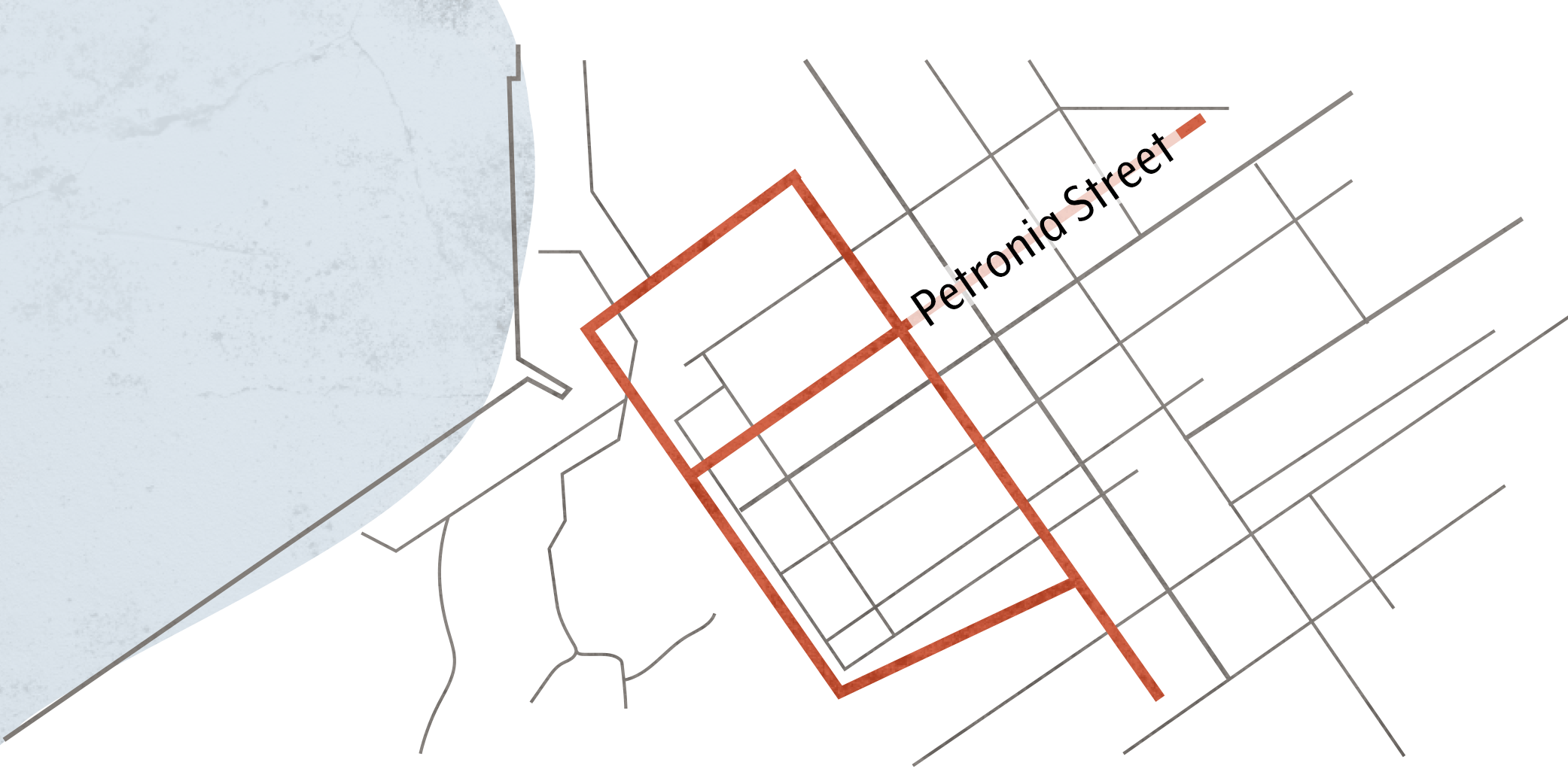

To understand the development pressures on Key West, it’s important to grasp just how uniquely challenged the island is when it comes to space. Spend enough time here, and the phrase two-by-four comes up repeatedly. That’s the island’s approximate size in miles, making it a minuscule dot in the Atlantic.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236251/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_28.JPG)

Things get more complicated when you factor in the man-made barriers. New buildings are restricted to a maximum height of 40 feet (recently raised from 35 feet), making anything over three stories a rarity.

In order to facilitate orderly evacuation during a hurricane, ROGO (the state-decreed Rate of Growth Ordinance) limits the number of new building permits available each year to just 197. And, as if that’s not enough, the huge military presence here means soldiers and sailors with generous government housing subsidies put an additional strain on the local housing market.

The influx has left realtors like Roger Washburn, who runs Island and Resort Realty, pretty busy. Many temporary residents from cities on the East Coast, who evaluate prices in terms of big city salaries, will spend exorbitant amounts on second homes, he reports. It’s driving up prices and shrinking inventory across the island.

The frenzied buying and selling has also made the lack of workforce housing a huge issue. According to Councilman Sam Kaufman—a lawyer, proponent of affordable housing, and longtime advocate for the homeless—many citizens, especially those who work in the service industry, are feeling the squeeze.

Ironically, the same forces that thankfully prevented Key West from being as battered by the housing crisis as the rest of Florida—a lack of surplus housing and space for development—have made the affordability crisis even worse.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236265/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_09.JPG)

A referendum to develop affordable housing at the Peary Court complex, a subdivision built by the Navy on the north side of the island, failed last year, and the city is currently looking at building on the adjacent keys. Kaufman says the land crunch means the only way to add room for those who want to live and work on the island may be embracing a bit of a loophole and simply adding more houseboats.

While affording a place on the island has become even more challenging, for many on Petronia Street, the subtle change in community presents an equal conundrum. They see the cultural richness of the island, the magnetic draw of the Conch Republic, slowly being drained.

Bahama Village is home to some of the island’s original settlers and their descendants. Once thriving, the area currently feels like it has been largely swept aside by gentrification and development.

/cdn1.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236269/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_08.JPG)

Seventy-seven-year-old resident James Chapman says, “People who lived here, who were from Jamaica and Bahamas, they were brought over here to build up this island,” he says. “Now they want us out of here. And there’s nowhere to go.”

In between making a few plugs for the Bible (“Think about it: BIBLE, or basic instructions before leaving Earth”), Chapman reflects on what Bahama Village used to be: A lively working-class neighborhood, where he worked a number of jobs—shining shoes, hauling ice, selling hand-painted bikes in the local flea market, even boxing at Blue Heaven for $10 a fight.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236271/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_24.JPG)

/cdn3.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236273/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_23.JPG)

Chapman and his neighbors and family—16 kids, 16 grandchildren, and eight great-grandchildren—have seen it all, including a heavy dose of real estate speculation. (Over the last few decades, realtors would come by and dangle $150,000 cash payouts to residents. Now, those same homes are selling for a million dollars.)

Sabrina Roberts, a fifth-generation resident who runs the Island Beauty Supplies store with her husband, says the surrounding blocks aren’t what they used to be. She spoke of schools and hospitals and boy’s clubs, of communal dinners and picnics, of neighbors talking all night, and progressive drinks from porch to porch in the early evenings. “There’s nothing for the kids to do,” she says.

“Everything is hotel, motel, Holiday Inn,” she says. “This island is going to sink with all the stuff they’re building. The Bahamian community is scattered.”

/cdn3.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236277/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_18.JPG)

And development is poised to accelerate. The $20 million Truman Waterfront Park, which will be located between the western edge of Petronia Street and the waterfront, is set to open by June 2018. The project will transform military land into a park and $4.5 million amphitheater, and lead to even more development in what’s left of Bahama Village.

One stretch along Petronia, chockablock with boutiques and restaurants, has been dubbed the “Greenwich Village” of the island. One of them, The Petronia Island Store, opened two years ago in an old storefront a few blocks down from Blue Heaven.

Filled with hand-carved crafts and scents with fancy names, it offers a high-end recourse to the tourist-oriented shops on Duval, reflecting the taste of owner and lifelong Key West resident Tyler Buckheim. She’s seen tremendous shifts in the neighborhood; a third of the buildings on the street used to be vacant.

Buckheim paints an idyllic picture of growing up in Key West. Her parents, artists from Detroit, lived on an even smaller nearby island when she was a kid, finally moving to the “mainland” of Key West when she was in middle school.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7236289/Blockparty_KeyWest_SM_KW_PETRONIASTREET_01.JPG)

“Gentrification has been happening a long time,” she says. “People have been saying that since the 1950s. I laugh when I hear tourists say, ‘I’ve been coming here for 12 years, and it’s totally changed.’ People complain they’re losing their Key West, and if anybody should complain, I should.”

So what’s a Key Wester, looking to live the dream while lacking the resources for ever-expensive property, to do? While the Caribbean harbors plenty of island escapes, another option involves heading back toward the mainland.

The first of 42 bridges deposits you on Stock Island, which still has a working commercial harbor. Mulysa’s already planning to move there with her partner, where she says she can find a more affordable place.