Dwell

Post

July 16, 2014

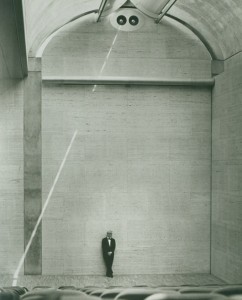

Louis Kahn at the Auditorium of the Kimbell Art Museum, 1972

The architect famously asked, “What does this building want to be?” when starting a project. In the case of this museum, Kahn incorporated skylights to diffuse natural light throughout as a way to illuminate the artworks.

A master of turning simple forms and classic motifs into extraordinary monuments, American architect and profesor Louis Kahn created a spartan body of work that’s become hallowed ground for his peers, influencing a generation. “It is important that you honor the material,” the perfectionist would tell his students, and for Kahn, that meant sculpting gorgeous curves and blocks of concrete and brick, massive structures large enough to inspire awe but still deft enough to play with light. His work, now the focus of an exhibition at the Design Museum in London, was inspired by a visit to Roman ruins when he was in his fifties, and still achieves the soaring spatial poetry of his peers without the advantage of more lightweight material.

An Estonian immigrant who settled into Philadelphia, Kahn took to drawing as a child, working with burnt twigs and matches when his family couldn’t afford proper materials. He was educated at the University of Pennsylvania, where he later taught before moving to Yale. His first commission, the Yale Art Gallery, was a template of sorts for later work, eschewing the International style for a new monumentality that juxtaposed airiness and emotionality with heavy forms of brick and concrete. As later works would showcase—from the tranquil pathways of the Jonas Salk Institute to the resonant silhouette of the National Assembly Building of Bangladesh—Kahn’s obsessiveness was not just over buildings, but in creating experiences.

Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth, Texas: 1972)

Recalling the arched construction of Roman architects, Kahn’s tubular museum design utilizes a row of cycloid barrel vaults, lined with reflective skylights that funnel natural light into the lengthy galleries.

Courtesy of: Robert LaPrelle

Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven, Connecticut: 1953)

This glass-and-concrete box in new Haven represents the first true realization of Kahn’s distinct style. While the cubic exterior stands out from its Neo-Gothic campus neighbors, Kahn’s interior is the real showpiece, with lattice-work ceiling of tetrahedral cast concrete and sunken triangular staircases that form dramatic descents.

Courtesy of: Elizabeth Felicella

Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park (New York, New York: 2012)

FDR’s uplifting wartime speech was translated into a sublime space for reflection by Kahn’s design, which features simple planes of granite forming a walkway that seemingly leads above the fray of New York. Completed posthumously, the park’s focus is “the room,” an open-air chamber surrounded by 12-foot-high walls of granite that stands as one of Kahn’s most transformative monuments.

Courtesy of: www.amiaga.com

Salk Institute (La Jolla, California: 1965)

Inspired by medieval monasteries, Kahn’s masterful example of symmetry reinforces Jonas Salk’s initial instinct; he famously met with the architect for consultative purposes but their conversation so impressed Salk that he knew he had found the right architect. The two rows of buildings are like curtains framing the ocean, and a simple dividing line offers as much serenity and contemplation as the horizon rising above the sea.

Courtesy of: John Nicolais

National Assembly Building (Dhaka, Bangladesh: 1962)

Originally meant as a Pakistani government building, Kahn’s monumental design became the seat of the government of Bangladesh when the country split in two. It’s as bold and commanding a symbol of young democracy as the world has ever seen; eight concrete modules envelop a center space cloaked in white marble, while the surrounding artifical lake provides natural cooling and a dramatic backdrop.

Courtesy of: Raymond Meier

City Tower Project (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Unbuilt)

While Kahn’s tetrahedron tower was never realized, his inventive suggestion of stacking pieces of precast concrete, a new typology of high-rise design, influenced future modular projects.

Courtesy of: Sue Ann Kahn

Jewish Community Center (Trenton, New Jersey: 1959)

Designed while Kahn was working on the Yale Art Gallery, this minimalistic structure appears to bring Roman design to New Jersey’s capital. A crucifrom of four square buildings, topped with triangular forms, adds a dramatic, sweeping entrance to a simple visit to the pool.

Courtesy of: John Ebstel

Library at Phillips Exeter Academy (Exeter, New Hampshire: 1972)

Kahn opened up the interior of this brick library with a ceiling clerestory, which allowed sunlight to flow in and colorfully contrast with the stone-and-wood interior. Illumination was a focus down to the smallest detail, such as the teak study corrals positioned in light-filled spots. It’s a fitting response to the design committee’s brief, which noted that “the quality of a library, by inspiring a superior faculty and attracting superior students, determines the effectiveness of a school.”

Courtesy of: Iwan Baan

Steven and Toby Korman House (Fort Washington, Pennsylvania: 1973)

Kahn’s often pegged with being architect who imposed his will on a structure, but in the case of this home commission, a rare residential work, it’s instructive to understand how far he went to make the home accommodate its inhabitants. The modified open floor plan respected the client’s wish to “be able to play touch football in every room,” and the two-story glass facade helped an allergy-suffering owner experience the outdoors.

Courtesy of: Barry Halkin