Article

Onion A.V. Club Chicago

September 2010

Link

Chicago’s first Food Film Festival pairs a program of provocative documentaries with a tantalizing array of food, including DMK Burgers and fried cheese curds, which still can’t top the fat content of artificial butter topping. While the “Hog Butcher of the World” label doesn’t exactly scream for a close up, plenty of films set here capture the city and its cuisine. Here are some of the top dining moments in Chicago’s cinematic history.

Lunch at Chez Quis, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986)

The preternaturally cool teen-philosopher, one of John Hughes’ greatest characters, proves his true guile in what might be one of the movie’s most underappreciated scenes. At a haughty French restaurant downtown called Chez Quis—a play on the down-market pizza parlor Shakey’s—the truant hero Bueller (Matthew Broderick) tries to score a table for his girlfriend Sloane Peterson (Mia Sara) and friend Cameron Frye (Alan Ruck), meeting with interference from an incredulous, snooty waiter. Bueller responds by scanning the reservation book and claiming he’s Abe Froman, later revealed to be the “sausage king of Chicago,” and doesn’t back down until he’s seated. The teens enjoy lunch, barely missing Bueller’s father on the way out. The true significance may be in the no-show; if the real Froman had a reservation, why didn’t he show up? Perhaps, as some commentators have suggested, Bueller planted the name as part of an elaborately constructed (not spur-of-the-moment) day downtown on Cameron’s behalf. The interior was shot in Los Angeles, and the exterior was a Gold Coast stand-in at 22 W. Schiller.

Soul Food Cafe scene, The Blues Brothers (1980)

Jake and Elwood Blues (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd) enjoy a few memorable meals on their quest to get the band back together, including a dinner scene (filmed at Chez Paul on Rush Street) where Belushi stuffs his face in a manner that recalls the cafeteria scene in Animal House. But the ultimate has to be the dry white toast and four fried chickens they order at the Soul Food Cafe. The brothers enter looking to re-recruit Matt “Guitar” Murphy and “Blue” Lou Marini, but so piss off Mrs. Murphy (Aretha Franklin) in the process, that she gets testy enough to belt out “Think.” Even though that song-and-dance routine was filmed on set, it and other scenes in the film were good evocations of Maxwell Street, a once-vital, now mostly gentrified neighborhood famous for its open air market, live performances by local blues artists, and Polish sausage sandwiches.

Dancing Zorba’s and wedding dinner, My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002)

Nia Vardalos’ Grecian family comedy was, in many parts, a tragic reminder of how easy it is for Hollywood to use stand-in cities for Chi-town. The incredibly profitable indie flick made the most of its small budget by filming in Toronto’s Danforth neighborhood, one of the largest Greek neighborhoods in North America, and featured exterior shots of venues from that city, like Pappas Grill. The main restaurant, Dancing Zorba’s, was shot at Simcoe and Pearl streets in Toronto. It was a massive missed opportunity to showcase Chicago’s own Grecian heritage, including the supposed introduction of flaming saganaki by the Liakouras brothers, Chris and Bill, at the Parthenon restaurant. With all the jokes about Greek cuisine, flaming cheese seems too good to pass up.

Baseball bat banquet, The Untouchables (1987)

De Niro whacks a disloyal associate with a bat during a climactic banquet scene shot at the Crystal Ballroom at 636 S. Michigan Ave. The scene was based on an actual mob assassination attempt; henchmen and thugs Albert Anselmi and John Scalise plotted a Chicago outfit coup, but Capone got wind and beat them both to death during dinner on May 7, 1929.

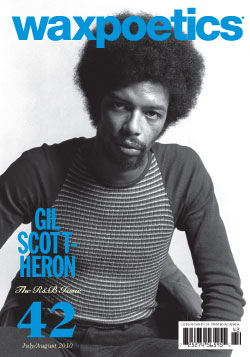

Sunday dinner, Soul Food (1997)

A tribute to the bonding power of a family meal, complete with a child narrator as sweet as his grandmother’s sweet potatoes, this film is filled with scenes where the camera lovingly pans over tables overflowing with traditional Southern fare.