Article

Chicago Magazine

January 2011

Link

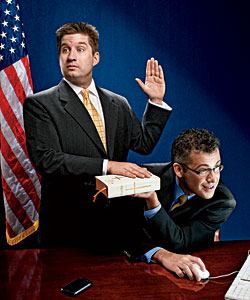

It’s fitting that a website about arguments emerged from one.

In the fall of 2009, the Chicago tech entrepreneurs Kevin Wielgus and Angelo Rago were at the Improv in Schaumburg when Rago’s then-girlfriend, whom he’d been dating for only a few weeks, received a phone call: Her parents were headed to the hospital. She rushed off; he stayed for the show.

At a bar later that night, Rago began receiving angry text messages: He was insensitive; his true colors were showing. Rago was amused. His girlfriend’s father had a bad case of hemorrhoids—hardly life threatening. Rago knew she was telling friends about how terrible he was, but from where he was sitting, he was in the right. Wielgus concurred. “I bet everyone in here would agree with you,” Rago remembers him saying. They then told the story to a crowd of fellow patrons, observing how the general opinion shifted as details emerged.

The situation inspired the duo to create Jabber Jury, an online courtroom that draws from such pop culture concepts as TV’s Tosh.0 and The People’s Court. They call the model “conflictainment.” Both parties in an argument—anything from husband-wife bickering to whether a friend dresses inappropriately—submit videos explaining their sides. The videos, uploaded to Jabber Jury’s proprietary system, form the basis of a case, and each party can add rebuttals and invite witnesses to submit video testimony. Registered users can leave comments, spread the case via social media, and vote on the outcome.

“We’ve all been guilty of being the voyeur and listening in on a couple at the next table,” says Wielgus.

Read more…