Article/Interview

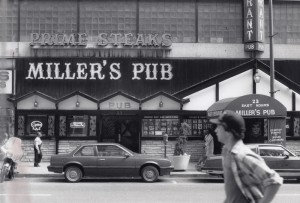

Eater.com

October 2012

Link

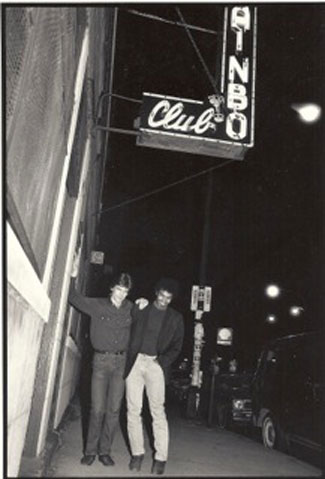

There are neighborhood bars—somewhere you don’t have to work to get a seat or the bartender’s attention, a dive that you like in a non-ironic way. And then there are bars that define a neighborhood. While the personality of Wicker Park seems malleable, as aspiring hotspots dilute the bohemian character that brought the area attention, it’s probably a safe bet that the role of local fixture will be played by the Rainbo Club, a shot-and-a-beer saloon on Damen at Division, for the foreseeable future.

Rainbo’s current incarnation started in October 1985. After past lives as both a polka bar and a watering hole in the Wicker Park of author Nelson Algren, the building was bought that year by Dee Taira and her partner, Gavin Morrison. The sprawling wooden bar, small white stage and red-vinyl booths have been maintained pretty much as purchased.

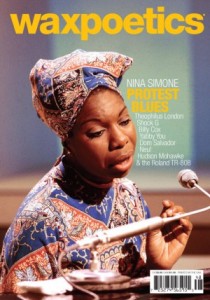

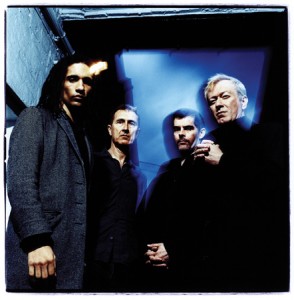

What changed was the clientele and staff, increasingly more artsy by demographics—as the ethnically diverse neighborhood became populated by artists, musicians and hipsters, and spots like the now-shuttered café Urbis Orbis—and by design, as ownership made it a point to support those artists with jobs and use the Rainbo’s walls as gallery space. In ’90s, the bar was a scene, a frequent hangout for local rock bands and musicians such as Urge Overkill, Tortoise and Liz Phair (the famous Exile in Guyville cover was taken in the Rainbo’s photo booth), and a fixture in the area’s social life. Here to tell the bar’s story are Taira, Phair and some key players from over the years.

Read more…